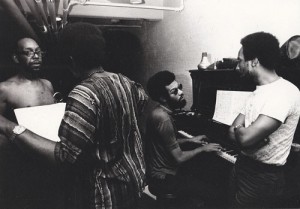

photo : Maxim François / Vision Fugitive

Cofounder of Strata East Records, Stanley Cowell started his career in Detroit, in the sixties, before moving to New York. There, the pianist played with great jazzmen, both from the young generation and the older one like Max Roach with whom he recorded an LP. After the great seventies decade, he decided to teach but never stopped playing and recording. For us, he goes back to his story while he will publish a brand new album in may, focusing on the Civil Rights movement.

Did you grow up in a musical environment?

Yes. Though my mother often sang around the house, my father played a little violin and piano, and all my sisters took piano lessons for about six years, there were no professional musicians in my immediate family beside me. A niece, Michelle, became a professional lounge singer and entertainer with a local Toledo group called the Murphy’s, who toured the Holiday Inn circuit in the US for several years.

How did the piano come into your life? And the jazz?

My parents seemed to like and listen to as many types as were available in my formative years at home: popular songs, 18th and 19th century European classical, blues, gospel, hymns and other church related music. We always had a good radio, record players, and we had a television set by 1949. They seemed less interested in the favorite music of my teenage years, rhythm and blues, and later, modern jazz.

Which music did you listen to in the 1960s?

I heard the classical piano music my two older sisters and I practiced, our dance music, blues, rhythm ‘n blues and jazz on the juke box at my Dad’s restaurant, the hymns and church musics from various churches in the neighborhood; the good jazz, R & B and blues records that found there way from the restaurant to the house; blues singers like Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf, Little Walter, Big Bill Broonzy; the growing number R & B groups like Clyde McFatter & the Midnighters, Orioles, Diablos, at night on the radio station WLAC from Nashville, Tennessee. These were the musics of my youth until I discovered bebop and modern jazz at age 13.

Who were your reference pianists?

Art Tatum came to my house once when I was six years old (1947). He was visiting family and friends and encountered my father, who invited him to our house. My father asked Art to play piano for me. Art said that he would like for me to play first. I played a piece from Book 3 of a popular piano study series, John Thompson. Art then played a Rodgers & Hart song, “You Took Advantage of Me.” That was my once and only “live” hearing of Art Tatum. I never wanted to sound like Tatum, but I have had to develop the technical ability to imitate him in certain “homage” performances since the 1980s. But in the 60s, my influences were McCoy Tyner, Cecil Taylor, Bill Evans, Wynton Kelly, and Phineas Newborn. I liked Andrew Hill, Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett and Herbie Hancock, and considered them my peers.

Your professional debuts: how was the musical « scene » in Michigan?

I chose to defer New York a while longer for the opportunity to finish my master’s at nearby University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, majoring in piano performance. I attended Michigan starting January of 1965, and again I was immersed in studying piano, practicing and studying classical music by day, but playing jazz by night. The venue for jazz soon became six nights-a-week at The Town Bar, Ann Arbor. I was featured pianist with bassist Ron Brooks’ Trio. Ron Brooks’ previous pianist had been Bob James, who at that time was incorporating a great deal of freedom and experimentation into the trio. That base was the perfect situation to which I contributed, building the trio into a tight nucleus that attracted musicians and audiences from Detroit, Flint, and Lansing, Michigan, as well as Northern Ohio. As the political and social upheaval of the Sixties was being felt and expressed in the music most intensely then, The Town Bar became a hotbed of radical and revolutionary music making, often enjoined by the visiting avant garde artists from the area. Many of the guests who sat-in to play were from The Detroit Artists Workshop, founded by poet and radical thinker John Sinclair and his wife, Leni.

I began to link more and more with musicians of The Detroit Artists Workshop: trumpeter/composer Charles Moore, composer Jim Semark, bassist John Dana, and drummers Ron Johnson and Danny Spencer. We hosted and participated in concerts with the New York and Chicago avant garde: Archie Shepp, Marion Brown, Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman from The Art Ensemble of Chicago, emanating from the American Association of Creative Musicians. Initially, we were barely tolerated by Detroit’s classical bebop-oriented veteran musicians, but given the social climate of frustration among blacks, artists and young people, we and they knew we were a part of the forces of change. We were eventually accepted and joined in our efforts by some of the local professionals like trombonist George Bohanon and pianist Kirk Lightsey.

Ironically, in the midst of the experimentation and rhetoric of radicalism, I achieved my goal, I learned Bach’s “Goldberg” Variations, performed my masters recital consisting of Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue in D minor, Schubert’s Sonata in A, D. 959, Chopin’s F minor Ballade, and Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin, and I received my master’s degree in performance in the spring of 1966. This accomplished, I returned briefly to Toledo before finally moving to Manhattan’s midtown far westside by early August.

Stanley Cowell Trio

“Blues For The Vietcong”

Why did you decide to leave for New York?

I came to New York try my skills alongside my musical heroes, Max, Miles, Art Blakey, Mingus, etc.

What did that change in your life? Your career ?

To be hired to play in the bands of my heroes and to travel the world performing became my career and changed my life.

In the 1960s, you were playing with strong leaders: Roland Kirk, Max Roach, Bobby Hutcherson, Marion Brown, Harold Land. What did they explain, transmit or give to you?

They each gave me the opportunity to learn their music and offered me encouragement to discover my musical personality–to play from my heart and soul.

You were associated with the “new thing” scene and nevertheless you published your first record in a classic piano trio formula. Did you separate those two aspects of your career : as a sideman and as a leader?

I had choices as to which style, era, direction, political influence, I might want to pursue as a sideman or as a leader. The « new thing » was about protest and politics for me ; whereas the audiences for which I often played preferred more traditional sounds.

You seem to prefer smaller bands and more particularly the trio. Why? What does that bring to a pianist and composer like you?

It offers a challenge to me to play more interactively with the bassist and drummer ; to debug compositional structures and ideas that could be for bigger ensembles in the future.

During Strata East record sessions, 1970s

You wrote “Travelin man” and played it in 1969 on your first record as a leader. You went on recording and playing quite a few more versions of it. Can it be considered as your anthem? Are you the « travelin man »?

Yes, yes, yes ! The vision for it came in a dream, though.

What about the UK recording ‘Blues For The Viet Cong’? Why were you in Europe at that time and how long did you stay?

I was on tour with Charles Tolliver in the quartet, « Music Inc. » and we stayed for about one month.

How (and when) did you meet Charles Tolliver?

We met at a rehearsal at Max Roach’s house because he was forming a new quintet. We became members of that band in 1967.

Why did you create Strata East together?

We created Strata-East Records to become our

own producers and distributors of our music, and to help other artist-producers control their own musical destinies.

“Effi” from ‘Members, Don’t Git Weary’ (1968)

Written by Stanley Cowell

What rôles did each of you have in the label?

Charles became more the person who handled finances, and I became more the expansionist who maintained communications with the growing number of artist-producers who affiliated contractually with SER. We both maintained relations with the media outlets on behalf of the company, and we stressed the idea to the artist-producers that all of us become promotional persons for SER as we toured and performed.

What was the philosophy of this collaborative label?

The concept was that of a condominium. Charles and I created the corporation–in other words, we owned the building. The artist-producers owned their recording(s)–in other words, they owned space in the building. A legal contract agreement was mutually executed by SER and the artist-producers.

During the last twenty years or so, Strata East has become an important reference for the younger génération of Jazz aficionados. How do you explain this late success?

The success was due to hard work by Charles and myself in handling the fabrication and pressing, shipping, getting distribution, radio airplay, and expanding the catalog. SER’s financial arrangement with its artist-producers was revolutionary compared to the traditional record company : 70% of net sales went to the artist-producers. They actually had the power had they been able to come together harmoniously with a development plan.

Would a label like Strata East have more chances of existing today?

Probably.

Do you believe that now, in 2015, Young musicians would have the same difficulties to become known or get signed, or has the internet totally changed the situation?

It seems to me the internet is the music business now for creative music, known as « jazz. » Pop music still operates in the old manner, signing artists and exploiting them via the new media possibilities.

Back then, you formed a team with Charles Tolliver : Music Inc… What was the aesthetic ambition?

The aesthetic ambition was to compose, play and extend the music of our great influences, mentors and innovators, while keeping the distinguishing features of the jazz tradition. Cecil McBee, Charles and I, each contributed music to the Music Inc. repertoire.

After the end of Music Inc, did you continue to see and play with Charles?

I played with Charles occasionally. I wanted to get off the road so I curtailed my touring to teach.

In 2015, you will be in concert with him for the opening night of the Banlieues Bleues festival in Paris. What will be the program, the spirit of the concert?

Powerful rhythmic expression and virtuosity in the style of our collective recordings and performances will be the spirit of this concert.

Both you and Charles Tolliver are somewhat underestimated by the general public, but very well known by musicians. How do you explain this gap?

Jazz and creative, improvised music as a whole has not been a popular music for many years. The sincere, knowledgable jazz fan obviously does know about us, otherwise we would not continue to be invited to record and perform. We have not declined in our skills but have become seasoned, like fine wine.

What about the Piano Handscapes project with Strata-East? Did the idea of 5 pianists playing together come from you?

Pianist, Larry Willis, suggested this idea, and it happened around the same time as other same-instrument collectives began to form in New York.

The whole Superfly Records team loves the tunes where you use the Thumb Piano (“Travellin’ Man” on your solo piano LP, the killer “Smilin’ Billy Suite” on The Heath Brothers album…)! When did you discover the thumb piano? Were you the first to introduce it in jazz records?

My sister, Dolores, gave it to me sometime in the late 1960s. I played it in the Music Inc. band, and entertained myself in hotel rooms as I traveled the world performing. I have used it for encores, on afro-pop and calypso type songs, and with the Heath Brothers accompanying some soft ballads.

You also released ‘Regeneration’, a more soul oriented LP… Why this title?

I was interested in world music and wanted to bring together some of my colleagues who played non-Western instruments, folk music, and jazz.

How did the session take place? And why did you not renew this type of experience with larger bands as opposed your former, smaller bands?

I had the freedom to create and produce what I wanted on Strata-East label but I wanted to improve small ensemble playing with traditional bands, work on my soloing in that context, and bring my composing skills more to the forefront.

In the 1970s you played and recorded a lot. And then suddenly, you stopped recording… What lays behind that choice? What changed?

I made a recording for ECM Records, and made four records for the Galaxy label (Fantasy-Prestige). Then I began teaching in the City University of New York system at Lehman College. I made this decision for the financial security that would allow me to marry and raise a daughter, Sienna. Consequently, I had the option not to take every gigs that was offered. I could avoid the smoky clubs, the lat-night life, and the negatives that life style could produce–health issues, etc.

You chose to teach jazz: what we can do, what we owe and what we are passing on? Is there anything that cannot be taught ?

I have a university master’s degree in music as a classical pianist, studied composition, music history and theory, but studied and learned to play and write jazz on my own. So, I was able to teach music history as well as jazz courses. It takes a person with certain acquired skills to transmit knowledge about any subject. I thought I had that potential, so when I was offered the professorship in 1981, I began learning something important to the transmission of the great arts.

If we have the patience, knowledge and wisdom from experience, we can teach jazz or any type of music or art. We cannot necessarily teach the finer points of creativity, style, sensitivity, compassion, value. But we can point the student(s) in that direction. It is up to their evolution and development of skills that will lead them to be able to personalize their craft.

What look to you take on new generations of jazzmen?

The skill level is high in many areas of the art of jazz. Of course, there are so many many branches and styles in the music today–admixtures, global influences, technology, etc.

Why has your music always found its roots in the blues?

I heard it as a child in my house and through my bedroom wisdom at night from a nightclub across the way. « Race » records were the popular source of music in my community. My father catered to musicians in his restaurant and later at is motel. He brought musicians to our home–including Art Tatum. Yes, blues inflection and form still influence my music, tempered by my other cultural and musical experiences.

Do you believe it is still the cement (unconscious) of the musical community in the US?

I think not as much as it was in the 20th century. There are so many students and performers of jazz who come from diverse cultures. Consequently, blues does not express what they feel, nor does it express what they want to express. All artists may be challenged like never before with the wide array of choices and directions. The question remains : How do I personalize this ?

Sometimes, during your career, you were contemplated for bringing in elements from the other Afro-American or African communities. Have you ever felt like you were making a “diasporic” music?

Perhaps, I will again. Right now, though, I am more interested in live electronic processing of my music as is heard on my recent SteepleChase CD, Welcome To This New World. I must mention that I have created a number of diverse works for orchestra, brass ensembles, woodwind quintet, choir, and electronic music since 1988, which have never been recorded. They are available to listen for free on my Google drive at should anyone be interested: https://docs.google.com/folder/d/0B2EgAWPq8mJqUHQxWklyR2c1b28/edit

You have just recorded a new record built around the civil rights movement in the USA. Do you think the musicians, through their compositions, are good witnesses of their time ?

Well, we try ! I suppose the real answer to that will not be known for many years.

How did you compose the repertory of this record ? Was it your idea?

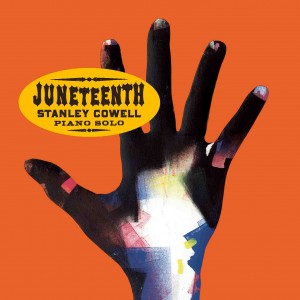

The idea came from two sources : The first came when Vision Fugitive producer, Philippe Ghielmetti , met with me in the US in 2005. He proposed a « Juneteenth » solo project for the label he was producing for at that that time ; the second came from a professor very knowledgeable of African American history suggesting that a composition written for the sesquicentennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, announcing the freeing of slaves in the US, would be an interesting project to undertake during my 2007 Rutgers University sabbatical. I did not pursue that idea for several years but began to compose it 2012, for concert band, choir, percussion and electro-acoustic sounds. Of course, the work was too large to be performed or recorded before I retired from the university. However, I was able to make a solo piano reduction of most of the score, titled, « Junteenth Emancipation Suite », and this is what I recorded recently for Philippe, along with a 17-minute improvised « recollection » of the suite and a couple of other pertinent songs.

His next record, on Vision Fugitive

Why did you decide to cover “We Shall Overcome”? What does this song represent for you?

It is the anthem of the civil rights era ! It represents faith, the ideal of non-violence, and solidarity with suffering peoples around the world who are trying to free themselves from oppression. Of course, some times this process can morph into violence. Being a jazz musician known for rearranging songs (obscuring the obvious) in order to present them in a new and creative way, I played the melody as the bass part of the song, reharmonized it, and improvised solos above it.

And you linked it to a gospel… Why the gospel? Is it the voice of speechless people?

The gospel piece was included on the « Juneteenth » CD to suggest and reaffirm the power of faith that played such an important role in the civil rights struggle in the US. Gospel and the spiritual song have been a powerful expression of speechless people/disenfranchised people in the US ever since black Americans applied their musics to the theoretical promises found in the Judeo-Christian religious texts.

“Travelin Man”, his classic

At the time of the civil rights movement, you were 20 years old. Were you involved in this fight?

No, not directly. I did not march in the South. But as a black person I felt the anger and frustration, and sympathized with those directly involved in the struggle. Having been born and raised in the North, Toledo, Ohio to be exact, and being in already integrated schools, and not sensing most of the discrimination or bias from white Americans, I led a studious life devoted to music, within a successful and harmonious family, in a predominantly black community. At the age of 19 until 20, I was a student in Austria, far from the civil rights struggle. Upon my return to the US, I became much more aware of the racial divide, discrimination and racism. If you follow the news today with the recent shootings of unarmed black males by police, it may seem that there has been no progress. Be watchful ! Despite having elected a black president, there are racists individuals, anti-black groups, and powerful people that resent the progress of African Americans. And they continue to work to undermine the milestones in economic, legislative and political areas.

Was the jazz community in the front line of the civil rights movement?

Certain ones like Billie Holiday by singing « Strange Fruit », Max Roach, Charles Mingus and Archie Shepp in their famous suites and compositions expressed their indignation with racism and their support of the civil rights movement. They were my influences and mentors toward including a protesting and political bent to some of my works and musical endeavors.

What is the role or the place of a musician in society: the griot? The watchtower? The activist?

I would reply : « all of the above. » We are not just artists, we are citizens of our respective nations, and ultimately, citizens of the world. In our own personal ways, and when necessary, in unity with others, we should add our « fuel » to the cleansing fire against injustice!

On June 19th, 1865 slaves of Texas were the first ones to become “emancipated”, Free ! 150 years later, the anniversary is still officially celebrated. 150 years later, were all the problems settled ?

Obviously not !

Thank you for letting me express somethings regarding my life in music, especially jazz, and my feelings on art, life and injustice. Looking forward to returning to Paris in March with Charles Tolliver and the Strata-East All Stars.

this interview is also published, in a shorter version, in Jazz News.