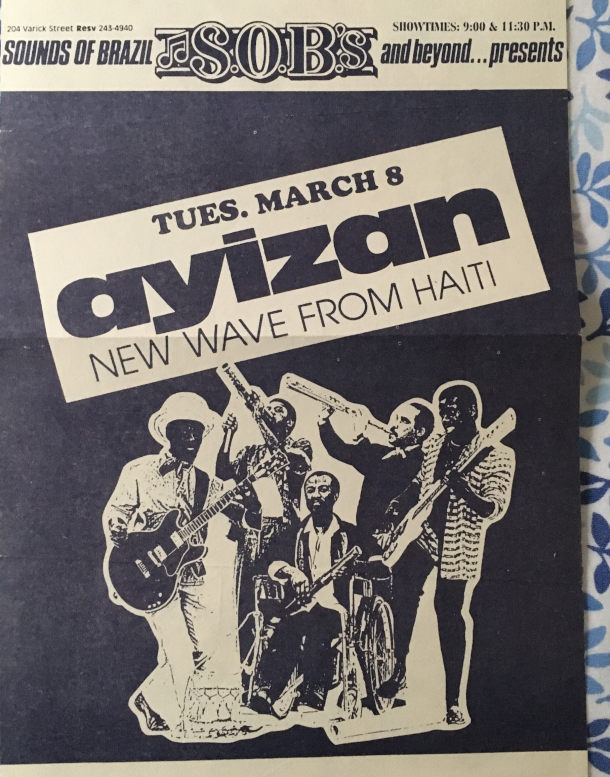

Ayizan: an ambitious music project marrying the haunting resonances of Vodou with the harmonic sophistication of modern jazz and progressive rock. We’re in New York, 1984.

By Uchenna Ikonne

November 2018

Ayizan: In the cosmology of Haitian Vodou, the goddess of the Earth, relocated to the Caribbean from her original home among the West African Fon people. She represents one of the four primal elements of nature, along with Loco (Wind), Legba (Sun), and Agwe (Water).

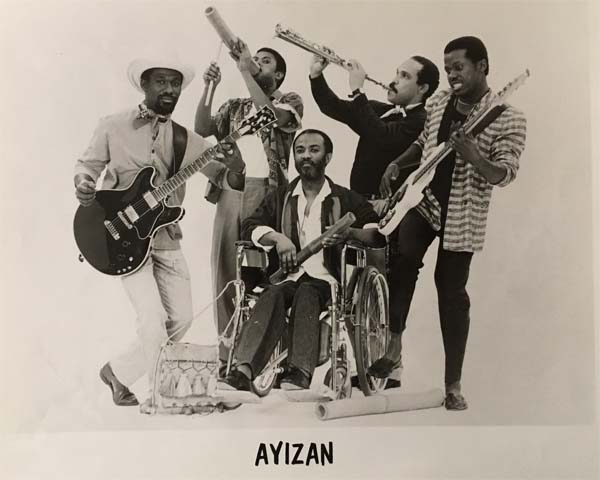

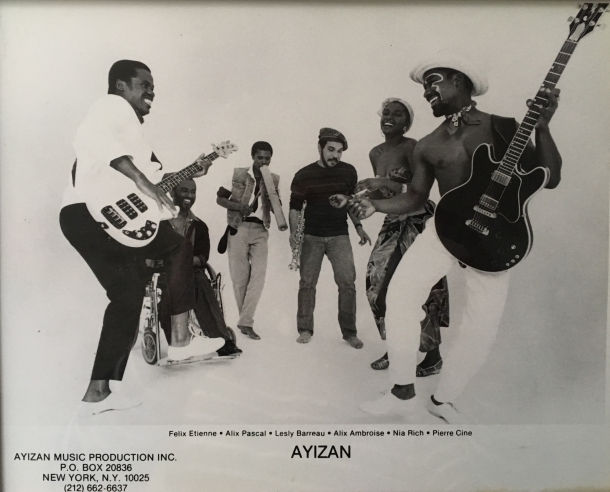

Ayizan: In the world of music, an ambitious music project marrying the haunting resonances of Vodou with the harmonic sophistication of modern jazz and progressive rock. The brainchild of Haiti-born multi-instrumentalist and arranger Alix “Tit” Pascal, the fundamental goal was to re-conceptualize the articulation of rhythm in Haitian popular music.

To say that rhythm is the heart of Haitian music is understate things: Rhythm is the heart, the lungs, the skeleton, the musculature, the pores, the brain and the soul. Indeed, Haiti’s perennially popular social music, kompa, takes its name from the Spanish compás—“beat”—for the steady, throbbing pulse of the tanbou barrel drum that has remained its central animating force for more than six decades. That basic beat, that compas direct has remained consistent, but there have been various attempts to complicate it, to problematize it, such as the efforts by the genre’s sainted originators Super Jazz des Jeunes to inject the traditional rara festival music into the kompa mix.

“I liked what our konpa founder Jean-Baptiste tried to do with integrating the rara,” says Pascal, “but I feel that it didn’t go far enough. Ultimately, the harmony was very elementary. Trying to mix the jazz format with the traditional Haitian melodies, it lost some of the pure feeling of Haitian music.”

Speaking from his New York home, Pascal goes on and on about the rhythmic minutiae of Haitian music. It’s a subject he has studied going back to his youth in the Port-au-Prince suburb of Pétion-Ville in the 1960’s. When he speaks of “the jazz format,” he’s not necessarily talking about a kind of music—at least not in this context—but rather a particular configuration of band.

“In Haiti, jazz is what we call a band that plays dance music with western instruments,” he explains. The term became popular in the 1930’s, during the US occupation of Haiti. American soldiers introduced big band jazz music, and Haitian musicians adopted the term to describe their own orchestras like Super Modern Jazz Guignard, Jazz Chancy, Jazz Annulyse and Jazz de Geffrard Cesvet, bands that employed the standard jazz ensemble in the performance of local music.

“But we listened to a lot of different kinds of music,” Pascal says. “The beautiful thing about Haiti is that there was no law to forbid radio stations from playing whatever they wanted. So we got to hear Cuban music, Mexican music, American and French stuff, too: Aznavour, Michel Legrand, Nat ‘King’ Cole.”

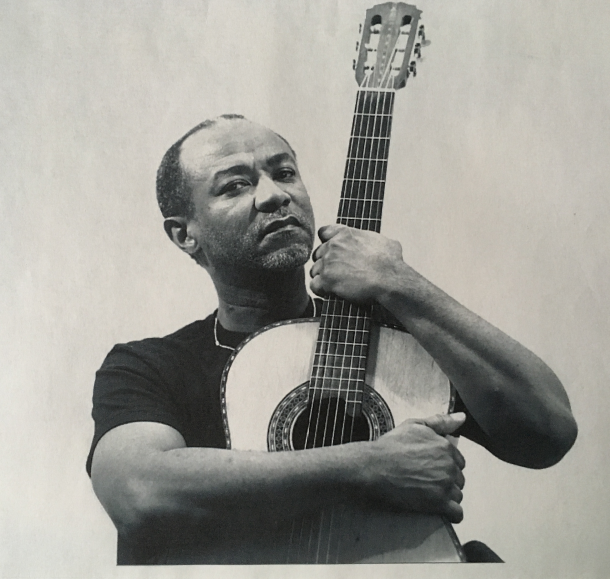

By the time Pascal was nine years old in 1956, Nemours Jean-Baptiste and his Ensemble Aux Calebasses were taking the country by storm with kompa. Young Alix meanwhile was binging on classical music and American jazz, teaching himself to play the congas, piano and bass. Eventually he took up the guitar, inspired by American jazzmen Charlie Christian, Wes Montgomery, Brazilian bossa nova pioneer Laurindo Almeida and Haitian guitarist Frantz Casseus.

“My mother wanted me to be a priest,” he says. “My sisters wanted me to be a brain surgeon. But I wanted to play music.”

By 1963, the landscape of Haitian music was radically altered by the increasing influence of western rock n’ roll. Pétion-Ville in particular became fertile ground for the emergence of young yeye and go-go bands aping Elvis Presley, The Beatles and Johnny Hallyday. Soon enough, though, many of these groups shifted their focus to playing a tighter, edgier form of new-wave kompa, spurring the development of a new musical formation: the mini-jazz, which stripped down the big band jazz format to a smaller, rock band-inspired format with two guitars, electric bass, horns, drums, percussion and keyboard. Mini-jazz became the new craze, championed by groups like Shleu-Shleu, Les Loups Noirs, Les Difficiles and Les Six As de Pétion-Ville, led by a teenage Alix Pascal.

Les Six As’ material stood out from the crowd due to Pascal’s keen ear for rhythm and harmony, and the group featured regularly on Tele Haiti, the country’s premier tv network. By 1966 Pascal was recruited to join Ibo Combo, the band of Hotel Ibo Lele, and with the group he began to experiment with mixing local sounds with jazz—not jazz in the Haitian band sense, but modern jazz in the vein of Bud Powell, Max Roach, Wayne Shorter, Thelonious Monk, and especially Miles Davis and John Coltrane and their post-bop experiments with modal jazz.

“The idea I had was basically modern jazz harmony mixed with the Haitian traditional songs that are pentatonic,” he says. “So we’re using modal harmony rather than tonal harmony, as Coltrane did in the sixties.”

Under Pascal’s direction, Ibo Combo became the most popular band on the scene and his career was on the rise. But that all appeared to come crashing down in January 1967. By this time, the dictator Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier had been in power for a decade, terrorizing the citizens of Haiti with his fearsome paramilitary police force known as the Tonton Macoute. Infamous for wantonly committing a range of human rights abuses from rape to murders, the Macoute had a tendency to project horrific acts of violence at will. Alix Pascal fell prey to this proclivity for violence when a Macoute randomly shot him in the back, leaving him for dead.

He survived, of course, but the bullet lodged in his spine slammed his promising career as a performer to an abrupt halt. He would be flown to the United States for surgery and physical therapy and return to Haiti shortly thereafter, paralyzed from the waist down and confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life. His disability would make it difficult for him to continue as a pianist, but his upper body and extremities were still fully functional and so he focused more on perfecting his craft as a guitarist. But even more importantly, he still had his mind, his ears and his ambitions to modernize indigenous Haitian rhythm.

He supervised the recording of Ibo Combo’s eponymous debut album in 1968, and then took on the role of an adviser, arranger and music director to the fast-rising new mini-jazz Tabou Combo, a role he continued even after he moved to the States permanently in 1969. Tabou Combo briefly broke up thereafter, but then reconstituted in the United States and they continued their relationship with Pascal, scoring under his direction an international hit with “New York City” in 1974. Pascal wanted to see the group road-test the avant-garde rhythmic concepts he had been thinking about back in Haiti, however they were a bit reluctant to go that far with him.

“They were already enjoying commercial success with their sound didn’t want to risk radically changing things,” Pascal says.

So he had to do it himself. So he created Ayizan.

Ayizan was at first the record label he founded, and on which he released his solo guitar jazz LP Determinations in 1978. But he was ready to turn it into a group project that would realize his grand vision for Haitian music. But first he needed to get musicians who could understand his language, and to find his chief collaborator on the project, he didn’t have to look very far.

“The guitar player was Pierre Cine, my cousin,” Pascal says. “He was a rhythm guitar player for Tabou Combo. Tabou Combo and other Haitian bands were using a little bit of the rara rhythm in addition to kompa itself. So I needed his skill, especially in the Tabou Combo style of rhythm guitar.”

Piano player Eddy Bourjolly brought more of the distinct sound Pascal wanted to reconfigure into a new form.

“I wanted the guitar and pass and piano to create a kind of dialogue you find in traditional Haitian drumming, in the Vodou style. It’s a kind of call and response. So while they were accompanying, I wanted them to maintain that essence and color of traditional Haitian music. The congas were there playing that rhythm as well but I wanted that rhythmic language to start with the piano, the guitar and bass even as they were playing the chords.”

Pascal explains that his goal was to avoid the same flavor that had marked other groups’ flirtation with rara, which had simply grafted the rara rhythm onto the pop kompa format, sounding more like a pastiche of Haitian traditional music than the true essence of it. “I took an approach so as not to disturb the color of the Haitian traditional songs. Others who tried it, what they did was a collage of traditional songs with some modern chords, but it didn’t really blend smoothly because the traditional melodies of Haiti tend to be modal. It took me a while to find a way to integrate the jazz harmony without losing the Haitian flavor. So even though we started the project in 1980, we didn’t actually put out an album until 1984.”

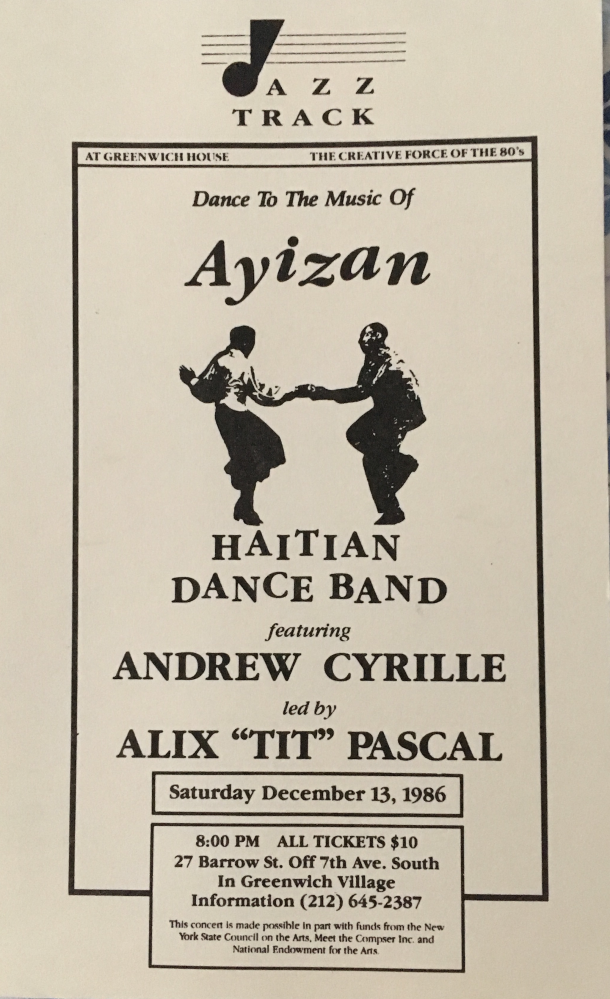

Work on the Dilijans album began in late 1983. At MSP studio in New York. In addition to composing, producing and arranging the project, Pascal made his debut as a lead vocalist. “I sang the album but I was not the one who was supposed to sing it,” he says. “The guy who I hired to sing left us about two weeks before we went into the studio in November 1983. I had been training him for a while because he didn’t know the harmony at first. He didn’t understand my pentatonic concept. And then he just left us, like that! The guys in the band told me that I should sing it myself. I said I’m not a singer! But I did it, playing the conga and singing the lead vocal at the same time.”

“The other guys meanwhile had trained themselves to sing background vocals while they played, which was not easy to do because of the complicated conversation they were playing with the bass and guitar. But we did not want to have too many additional singers. We didn’t want to have too many people on the stage, like a choir. We wanted to have the presentation of a rock band. But I didn’t want to play like a rock band, just banging on the beat. The rhythm had to be more subtle.”

The result was like nothing else coming out of Haiti or the Haitian exile community in the US at the time. Dark, mystical, lyrical and abstract, with its otherworldly shifting rhythms, Dilijans came off like a Haitian version of Bitches Brew. The album sounds less like a stylish mini-jazz performing in a hotel dancehall than like a cry of ancestors emanating from the spirit world to lament over the complications of modern Haitian society.

“When we were recording in the studio, the engineer Ben Rizzi—who has passed away—was very interested in what we were doing. He said that he had never heard so many layers of rhythm that go together in one shot! He had never seen that before. He was very impressed with what we were doing and he invited many people from big labels to come and check out what we were doing.”

The early eighties were a fortuitous period for bands like Ayizan. In the aftermath of Bob Marley’s death, major labels were scrambling to create the next “Third World Superstar.” A plethora of “exotic” artists from the Caribbean, Africa and beyond were signed and packaged in a rock audience-friendly presentation, creating a booming market for “World Music.” CBS/Sony in particular expressed interest in Ayizan.

“But we had a small problem,” Pascal says. “It was not what we were doing musically but the language in which we were doing it. CBS told us that if we were singing English, they would definitely pick it up.” This particular condition proved to be a creative crisis for Pascal.

“It’s not so much that we didn’t want to do it, but when you’ve written all this work in a language, kreyol, in a culture…” Pascal trails off, even more than three decades later still trying to come to terms with the momentous artistic decision that faced him. “First of all, the subject matter that I was dealing with in the lyric, it was based in social consciousness, contrary to what other groups were doing which was all ‘Hi baby, hi baby, I love you.’ Really, there were a lot of Haitian artists doing socially conscious lyrics because our country has a lot of political problems.”

But the bigger problem was less about altering the substance of the lyrics but rather about how changing the language would compromise the carefully crafted rhythm and tone of the sound: “To write the lyric in the first place in kreyol so that it swings with the music… it’s a skill in itself. So then to change that and present the lyric in English… It’s a challenge. “

“I thought about it, I even tried to take a few songs and try to translate them to English. It just didn’t work. It would have to be rewritten completely to find the right English words that would maintain the correct rhythm pattern. And since we were in the middle of production, all the words were written already, and rewriting them… It would have been a lot of work.”

Pascal went ahead and released it himself on his Ayizan imprint and despite the relatively limited exposure, the album attracted significant acclaim and a demand for the concerts, primarily in the tri-state area. Still, Ayizan would not quite hit the big time.

“It was hard,” Pascal says. “What we were doing was different so it was a challenge. Music was attractive but the business didn’t always work out. It’s not easy when you’re trying to start something new. It’s almost like a young marriage in which you’re fighting all the time.”

“The band changed. Guys come in and go out, except for the bass player, Félix Etienne, the guitarist Pierre and me, who were the key members. We were trying to raise money to make another album, but we were getting like maybe $800 for a show, and that mostly went into buying instruments, getting a van and things like that. Me, the guitar player and the bass player never made a penny. We would pay the other musicians maybe $100 each.”

Interest from record companies still floated around Ayizan, but Pascal remained unwilling to concede on the condition that the songs be performed in English. And worse yet, some of the labels wanted the group to change their style altogether. “They wanted us to play reggae,” Pascal scoffs. Not seeing that as an option, Ayizan would continue to work independently of the music industry infrastructure, even as the tribulations gradually chipped away at the band.

“We tried to keep it going,” Pascal says, “but by 1987 we found ourselves with no more musicians. Just the three of us and a girl who sang and danced with us on stage.”

“We finally called it quits in 1989.”

In the thirty years since the end of the Ayizan project, Alix Pascal has remained active, largely in the jazz realm. But he still dreams of resurrecting his unique rhythm project. “I still have a lot of compositions I wrote for the second album that never happened,” he says. “About three, four years ago , Pierre came back to me and said ‘Man, all those material we had in the eighties have been wasted. Now we’re more mature… Let’s work with them. So that is what we have done.” Ayizan, he assures us, will soon rise from the Earth again.

Uchenna Ikonne

August 2019