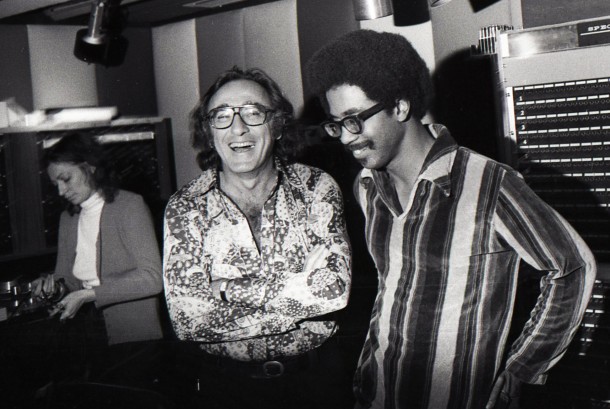

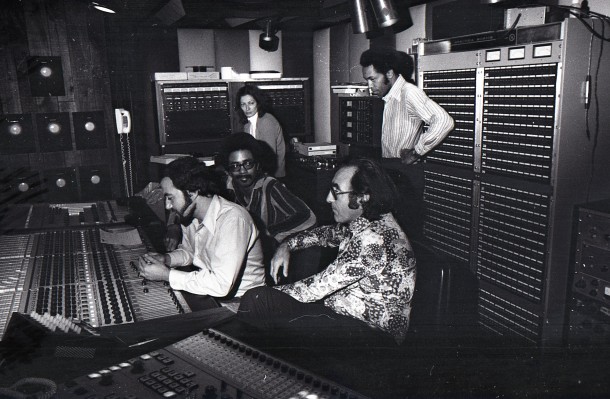

Bob Shad with Reggie Moore, 1972

Bob Shad was one of the key jazz producers of the 20th Century alongside Creed Taylor, Orrin Keepnews, Bob Thiele and Nesuhi Ertegun. He left an unforgettable mark on music across many genres, producing more than 800 albums over a 40 years career and recording many Giants in the process. “He was not just commercial, he recorded mainly what he believed in.”, said critic Leonard Feather. Born in New York on February 12th, 1920, Bob Shad got in the music business in 1946 working first for National Records and then for Savoy Records as they bought National. It was the beginning of a long and fruitful journey which saw him work with Charlie Parker on the legendary Savoy Sessions, set up EmArcy Records in the 50s and produce a 7” single in 1958 by The Jades featuring a 15 year old guitarist named Lou Reed. Oh and he recorded Janis Joplin’s first LP in 1966 with Big Brother & The Holding Co.

The list of luminaries Shad recorded or discovered is endless: Lightnin’ Hopkins and Art Blakey, Max Roach and John Cage, Cannonball Adderley and The Platters, Sarah Vaughan and Quincy Jones. An entrepreneur at heart, he founded a new label, Mainstream Records in 1964 producing jazz, psychedelia and soundtracks. In 1971, he started the cult Mainstream MRL 300 series featuring the radical sound of the early 70s recorded by a new wave of young robe-dressed jazzmen, influenced by both the modal sound of the New Thing and the funk of Sly Stone. Shad didn’t restrict his productions to one particular genre and also recorded young soul divas such as Ellerine Harding, Maxine Weldon and above all Alice Clark, whose eponymous album mixing soul with Ernie Wilkins’ funky big band arrangements has become an absolute classic.

Just out on WEWANTSOUNDS, is “Feeling Good”, a 2-LP selection from the rich Mainstream catalogue, filled with mouth-watering, Fender Rhodes-drenched deep jazz, soul and funk. And we’ve heard there is a second opus already in the pipeline. More than thirty years after his death, it is essential to rediscover the legendary Bob Shad, a maverick jazz producer and passionate music man from the glorious days when vinyl was king. We talked about the great man and his legacy to his grandson, who is none other than comedian, producer and filmmaker Judd Apatow. Cult.

You were born in 1967 just a few years after Mainstream Records was launched and the year your grandfather released the Big Brother/Janis Joplin album. Was the music he produced part of your childhood’s “soundtrack”?

Absolutely, at home when I was a kid, we listened to Jazz and to the music Bobby produced. I don’t think I fully understood what it was about until I was in high school when I started deejaying at my high school radio station and had a jazz show. At which point, I decided to visit my grandfather in Los Angeles and my hope was that, for the first time, I would be able to talk about all the work he had done because I was old enough to understand. But sadly he died of a heart attack just before I made that trip so I was never able to have that conversation with him.

What relationship did you have with him when you were growing up? What sort of grandfather was he and what was he representing in your family?

As a kid I saw my grandfather all the time. My father actually worked at Mainstream Records for my grandfather so I would visit them a lot at the label. Bobby was a legend in the family for all he had accomplished. He was a really funny guy and had a great sense of humour. He loved to give you a “hard time” and he was so passionate about music and what he’d done.

Bob Shad was a cult producer and we could say the same about you in a way. How did he inspire you?

He was such an inspiration because he was a self-made man. He was some poor kid in New York who cobbled together enough money to hire some jazz musicians and record them. Then he had records made and went to sell them to record stores himself and that was in the 40s. Then he opened a record store and started his own label. What’s amazing is some of the people he recorded when he was very young turned out to be Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. It all happened just because he loved the music so much. He had no ‘way in’ in the business. He didn’t know anyone and just did it. For me that was a great inspiration because I thought ‘oh you can do what you want to do in comedy, you just have to do it’ so I started interviewing comedians when I was a very young and I was writing jokes for them. I also did stand-up comedy in high school and that was all because I knew my grandfather had done the same as a young man. For instance, he went down south with his tape recorder and recorded all these blues artists on their front stoops. He was a real innovator.

You’ve namechecked him in your film “Walk Hard – Dewey Cox Story” by naming one group in the film “Bobby Shad & The Bad Men”, a nod to the album he released on Mainstream Records. Also you have used several tracks from Mainstream Records in your soundtracks along the years. Do you have any favourite track or album from the catalogue?

I get a kick out that album, Bobby Shad & The Bad Men where he would cover rock songs with a 65 pieces orchestra, it’s such a fun album. I grew up listening to the first Big Brother & The Holding Company record featuring Janis Joplin because the family talked about it all the time. My family would say: “Janis Joplin is the best singer ever and your grandfather found her before anybody else in 1966”. I have the letter of intent hanging in my office dated Sept 7 1966 saying she was going to sign with him. So people talk about Columbia boss Clive Davis discovering Janis Joplin but my parents always said: “Well actually not, your grandfather did. She did her first album for Mainstream Records”.

There is also a legend in the family that Bobby tried to sign Elvis Presley. Apparently he was down South and he called Mercury, the label he worked for at the time, to tell them to sign Elvis but it took a very long time to get approval and match the sum Colonel Tom Parker, Elvis’ Manager, was asking for. So by the time Mercury gave the greenlight, Elvis had already been signed by RCA for 40.000$. I always enjoyed hearing the stories about who Bobby didn’t sign. People he had seen when they were really young and didn’t pick, like the Grateful Dead. Another one was Bob Seeger. Bobby would say: “Ah yes I didn’t sign him!”

Hadley Caliman, Alice Clark, Harold Land

There is one album, The Alice Clark one from 1972, whose reputation has been growing exponentially over the last years as one of the best soul albums of all times. It’s beautiful and got a very cinematic feel. Do you have any plans to use more tracks from the Mainstream vaults in future productions?

I regularly use tracks from the Mainstream catalogue in all of my films. I always have jazz in there, also rock and blues tracks, I’ve used Ted Nugent’s group The Amboy Dukes, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee. It’s a fun nod to my grandfather and his work.

Bob Shad seemed ahead of his time as he championed African American artists (jazz, blues, doowop…) producing them back in the 40s at a time when it wasn’t common. Has he passed on to you his passion for jazz, funk and blues or made you appreciate these genres more, in today’s context?

I’m a big fan of jazz, funk and blues. I’m certainly not as knowledgeable as he was but he made me appreciate the music and made me more open in having eclectic tastes in all arts. The best thing about Bobby is he had no boundaries with the label: he produced rock ‘n’ roll, blues, jazz, avant-garde with a John Cage album! He just loved music. Also Mainstream was a vital label in the 70s when jazz was not as popular as it had been. Mainstream was one of the few labels who were still making original jazz. And he put out some comedy albums as well which I really loved as a kid, like these Dickie Goodman records where he would be a reporter asking questions and the answers were little snippets of famous songs. There were really funny albums.

Your grandfather fought hard to impose photos of black musicians on album covers…

Yes way back then, Record labels didn’t want to carry records if they had pictures of Black artists on the cover and Bobby would refuse this. In his own way he broke down a lot of barriers by loving this music and by pushing the world to hear it. He felt that these great Black art forms deserved much more respect.

Bob Shad at Record Plant Studio with Reggie Moore and Carmine Rubino

Your films “Knocked Up” and “This is 40” films with Paul Rudd as a Label owner feel very authentic. You were too young to work at Mainstream but have you had any record label experience in the past?

I know the music business from my family running Mainstream Records. They’ve been putting out music through the years as the formats changed: from vinyl to CDs and now streaming and digital downloads. So I do understand the work and the struggle to keep a label going. Also My high-school friend Josh Rosenthal who was deejaying with me at the high school radio went on to work at Sony Music for many years before starting his own label, Tompkins Square Records, a great specialty label, so I’ve seen his journey over the decades and some of that have inspired me as well.

My love for music and artists who are not necessarily the most commercial ones has always been there. Loudon Wainwright III is one of my favourite artists so I had him score Knocked Up. Graham Parker who stars in the film was very keen to satirise the struggle of ageing rockstars. Also we made the movie ‘Pop Star’, a mockumentary with Andy Samberg and his comedy trio ‘The Lonely Island’. And of course ‘Walk Hard The Dewey Cox story’ about a fictional rock’n’roll star; so I always go back to music.

Thanks to the new compilation “Feeling Good – The Supreme Sound of Producer Bob Shad” a new generation hooked on jazz, funk and hip hop are going to discover the great productions of your grandfather who was a fiercely independent music guy. Do you think independence remains the key for cultural creativity and diversity?

I’ve always admired people who go their own way. Some people are very good at making Top 40 music but I’ve always been a big fan of artists who express themselves and don’t think too much about what’s popular in the moment. I just participated in a tribute concert to Warren Zevon. Jackson Browne put the event together and everybody sang songs by Warren. I’m really interested in artists who make music from their heart and don’t worry too much about the economics, Bod Dylan, Loudon, Jazz artists…

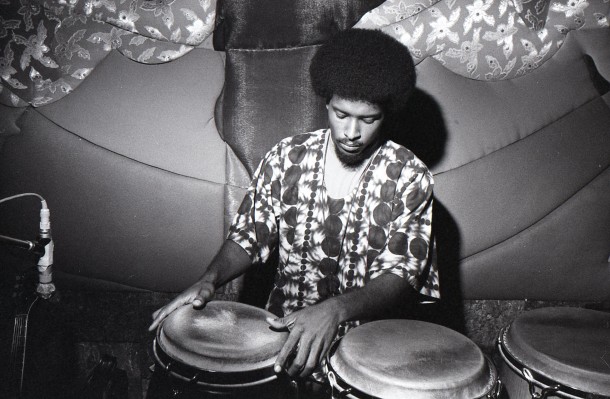

Mtume for Buddy Terry sessions

Mainstream Records tracks have been sampled many times by the likes of NWA’s Easy E or A Tribe Called Quest. Recently, Chance the Rapper has used a sample of the track “Red Clay” by Jack Wilkins in his track “Nana”. His lyrics are pretty “green” as we say in France. Did you meet with him? How did it go?

We didn’t talk about that specific sample when I met him but I’m a fan of his work and I feel like he’s evolving quickly into one of the greatest rap artists in the world. Obviously some of his earlier work is edgier (laughs) but his current work is very spiritual and inspiring so I thought it’s great that he’s used a sample from the Mainstream catalogue.

Late in his career, Bob Shad decided to move to Los Angeles and go into Film production. You’ve followed a similar path in a way with comedy as a launching pad instead of music. Are there any cool film projects he was involved in during that later Hollywood period or any anecdote?

Bobby was working with director Frankenheimer for a few years and I know there was a moment when they were trying to get the movie “Being There” made. My grandmother told me they had the rights of the book for a while. They didn’t manage to get it made, Amoeba Records ended up directing it, but at least I know they had good taste!

Last question, do you collect records and LPs in particular? Do you have any favourite shop in Los Angeles?

I hadn’t been buying vinyl for a long time but in the last year I bought a whole new sound system with a turntable and have just started the vinyl journey again. I hadn’t listened to vinyl for so long and I put a Led Zeppelin album on, it felt like they were in the room. I thought “My god what have I done with my crappy sound system for the last twenty years!” It’s fun to go in record shops and search things out. There’s Amoeba Records in LA of course. There is also a great shop in Santa Monica, The Record Surplus, we shot a scene in Knocked Up there actually.

This interview was originally published by Liberation, in a shorter french version