Here’s a record that sounds like nothing else – a unique cross between Highlife and Afrobeat – the type that will never sleep on your record shelf for too long. Enjoy!

When most people think about the music of Nigeria, the first thing that comes to mind is probably afrobeat, the darkly funky African jazz stew popularized by bandleader Fela Kuti, himself a Yoruba from the southwestern region of the country. Or perhaps they might mention other Yoruba musicians such as King Sunny Ade and Ebenezer Obey, the twin pillars of the southwestern juju style. Maybe their thoughts would glide more towards the eastern extreme of the country, where Igbo highlife stars such as Stephen Osita Osadebe, the Oriental Brothers and Oliver De Coque have made a mark upon the arena. More imaginative thinkers might look northwards to cite Hausa and Fulani griots like Dan Maraya Jos, Alhaji Mamman Shata and Alhaji Musa Dankwairo. It is rare though, that the spotlight is leveled towards the mid-western region of the region of the country, the territory encompassing the modern-day Nigerian states of Edo and Delta. Edo in particular boasts of a wealth of musical traditions that is both deep and broad, yet shamefully underexplored; and among this assortment of musical traditions, one of the richest is the music of the Afemai, or Etsako people. And in the field of Afemai music, the undefeated champ is Alhaji Waziri Oshomah.

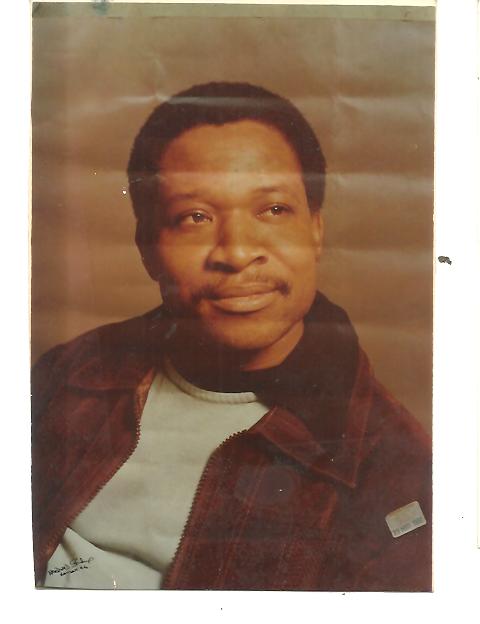

Afemai music has for some time been the best-kept secret among the more discriminating connoisseurs of Nigerian highlife, and for many it is almost addictive, driving them to search madly for more and more music in this semi-obscure style. It’s hard to describe exactly what makes this music so intoxicating: it is in parts gritty, hypnotic, ecstatic, lilting, soulful… but when words fail, the adjective most would employ to describe it is deep. The difficulty of discussing it is compounded by the fact that the music does not exactly have a generic label or an emblematic figurehead to lead it in that way that, say, Fela serves for afrobeat. However, Waziri Oshomah—“the Etsako Super Star”—generally functions as the most accessible and consistently rewarding entry point into the wondrous world of the Afemai sound and he has reliably acted as its ambassador for more than 40 years.

Waziri Oshomah was born Isah Sule in the mid-western town of Osomegbe, in 1948. Osomegbe is situated in the territory of the Ekperi clan, and its population is culturally and religiously heterogeneous. “We are about 40% Christian, and 60% Muslim,” Oshomah says. “My family is Muslim.” His family also happened to be musically oriented, participating in the performance of traditional social music. “My parents were composers,” he remembers. “They were also lead vocalists in such local cultural groups as Agbi, Izi, Agie, to name a few.”

Given his musical familial heritage, young Isah took to performing quite early in life, by age 7 already leading the school band at St. Mary Primary School, Ekperi. While he had a natural interest in the indigenous cultural music of his community, he was obsessed with the new music capturing the hearts and minds of the young generation: highlife. “As a small child, I used tossing verse by verse or stanza by stanza, records sung by highlife musicians like Bobby Benson, Victor Uwaifo, Eddy Okonta and I.K. Dairo.” Drawn to this music, Isah had already started attending and performing at nightclubs before his tenth birthday, much to the consternation of his devout parents.

“My parents now saw me as a spoilt child”, he says. “They later disowned me because they felt I will sacrifice my Muslim religion for music.” However, contrary to his parents’ fears, he did not drop out of school or out of the Islamic faith. He successfully completed his high school education at St. Andrews Secondary School, Fugar and secured a respectable government job as a gauge reader with the Ministry of Water Services and Hydrology. Still, he could not escape the lure of music.

By 1965, Isah Sule had created an alternate identity, dubbing himself “Waziri Oshomah” as he performed locally with traditional percussion orchestras while still maintaining his workaday lifestyle as a civil servant. By this time, the sphere of Afemai music had slowly begun to expand beyond its immediate locality thanks to the rising popularity of Anco Momodu, the first Etsako bandleader to make a significant impact on a national level. Momodu had actually made it to the big stages, performing in clubs in Lagos. Cardinal Rex Jim Lawson—Nigeria’s biggest highlife star of the day—was a fan, and had even started integrating elements of Momodu’s repertoire into his own music. Anco Momodu’s success indicated that there was a future for this odd music from the obscure Afemai community and his was the hottest local band in the Edo region. In 1967, Waziri Oshomah joined Momodu’s group as a singer and keyboard player.

Working under Momodu gave Oshomah a taste of what life as a professional musician could be—he got to travel to different towns, and even got his first exposure to the recording studio as he participated in the records Momodu’s group made for the local Benin City label Akpolla/Agbede, the same imprint that boasted Rex Lawson amongst its roster. However, Oshomah felt that the music could be taken even further. After the end of the Nigerian civil war of 1967-1970, tastes had begun to change: the rustic, low-fidelity aesthetic of traditional sounds was starting to feel quaint as audiences demanded state-of-the-art sounds like the amplified bass guitar, electric organ, funky drum patterns. Oshomah decided that it was time for him to break out on his own and pursue a new direction for his music.

Quitting both Momodu’s group and his civil service job, Waziri Oshomah formed his own Traditional Sound Makers band in 1973. The group started as a rather shambling, low-key affair: “We did not have equipment”, Oshomah remembers. “When we played, we didn’t have professional amplifiers. We used a locally-built amp that was powered by ordinary torchlight batteries.” Despite these shortcomings, the Traditional Sound Makers were still able to score a contract with Decca West Africa Records and release a single “Agiode Ofe Emo Mie Ise,” which did well enough to allow Oshomah to acquire his first set of modern instruments the following year. He then set about a series of experiments with the goal of modernizing Etsako music for a new, broader audience.

Sir Victor Uwaifo had been a revolutionary figure in the mid-60s, as the first musician to add a modern sheen to the traditional music of the Edo region by infusing it with highlife and rock n’ roll. Oshomah idolized Uwaifo and closely patterned himself after him (even taking on the honorific “Sir” himself). “I wanted my music to speak to both the old and the young”, says Oshomah. “At that time, what was popular among the youth was soul music. So I mixed some of that with the traditional sound. Or other modern sounds like reggae, rock, I would take all of these and mix them into my music.” He also drew inspiration from Fela, whose new afrobeat was the hottest thing in country, illustrating that you could create a modern funk-oriented style that was still firmly grounded in the bedrock of indigenous folkways.

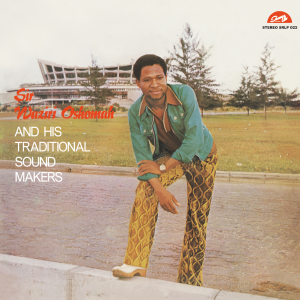

Sure enough, the fusion paid off and Waziri Oshomah’s national popularity soon dwarfed even that of his mentor Anco Momodu. His profile rose considerably when he joined the stable of the ascending juju-oriented label Shanu Olu in 1978 and over the next six years released a five-volume series of eponymous albums that received strong national distribution. Superfly Records is proud to present here, reissued for the first time ever, the third installment: Sir Waziri Oshomah and his Traditional Sound Makers Vol. 3.

Vol. 3 is certainly Oshomah’s tightest, most focused effort as it distills the varied elements of his influences to their essence that somehow exceeds the sum of its parts: Simmering grooves built from afrobeat-inspired basslines, palm wine guitar chords, space-age electric organ lines, honking R&B saxophone refrains, all of them laid over the solid foundation of the distinctive Etsako rhythm, and held together by Oshomah’s confident, plaintive vocals. It’s quite a concoction that serves well either for dancing or for quiet reflection.

While his Shanu Olu albums are perhaps his most popular, Waziri Oshomah did not stop recording after parting ways with the company in 1985. In fact, he continued to produce records on an assortment of regional labels as well as on his own imprint. He remains busy and in demand even today, and while he cannot definitively state exactly how many records he has made throughout his career, he estimates the figure to be around 150. And he takes his position as the long-running Etsako Super Star very seriously indeed.

“I call my music oyoyo”, Oshomah explains. “It means ‘the best.’ In my community, when there is a feast of masquerades, the best masquerade is usually called oyoyo. And when that masquerade plays, nobody expects any other to come after it.” While Waziri Oshomah’s music is most certainly the best, we hope that more will come after it, and that it will serve for new listeners as an introduction to the Etsako sound, the gateway through which they might discover more and more of this fascinating realm of music.

Liner notes by : Uchenna Ikone (Comb & Razor)

i have been listening to his music since 1974, though am a yoruba.man ijebu tribe to be precise, nice music

Really interesting story

Edo baba

These where really musicians, not what we have today.

A good for we the indigenous that are of the new generation

good sir

I first heard this just a few weeks ago in the Jazz Hole in Lagos. The proprietor noticed me digging it, and said “Heavy”. “Very heavy” I agreed. It’s so rich; laden with history and pathos. I can’t believe that we produce so much excellent music in Nigeria; we are truly blessed.

I don joke with his music he is my favorite among etsako

i always love all waziri music and he and my father finished school together .iam an edo man from atte

My father always talk about Waziri as a legend. So I took my time to listen to his songs.

This man is indeed a great legend.

I always love waziri music and he has alot in the music industry. Osomhegbe ekperi son

I cant understand a single word he says but my love for Afemai music was born listening to a show called Afemai on Ray Power Lagos back in the mid 90s.

I couldnt understand the language but the lady presenter’s voice kept me captivated and I also liked a certain musical instrument (not sure what it is) that was always present in the songs.

I moved abroad and forgot about

Afemai music until my dad died in 2015. I started to look for music that brought back nostalgia about the times I spent with him and I found Afemai again. It reminded me of those Sunday drives back home from church listening to the Afemai show.

Now I dont think my day is complete if I dont listen to at least one song from Waziri Oshomah. Such a shame that I dont understand the language but maybe that is a blessing as it keeps the music fresh and I can listen to the same songs over and over again.