Back in 1989, green activists and musicians Desmond and Sheila Majekodunmi left a unique musical testimony to their fight for the preservation of nature. This is how it all happened.

By Uchenna Ikonne

November 2018

When Sheila and Des Majek released Green Leaves in 1989, the husband-and-wife musical duo were certain that it was an LP like none other that had ever come out of Nigeria. They were right. Musically, it’s dark, dubby synth-pop and slick, slinky afro-reggae grooves stood out from the dominant standards of the day. And then there was Sheila’s voice; she sounded like nobody on the scene, combining the cool poise of Sade with the incandescent warmth of Chaka Khan. But what really distinguished it was its thematic focus. Its songs—with titles like “Mother Nature,” “Korrup Forest (In Africa),” “Green Leaves,” “Let Us Plant A Tree Today”—maintained a single-minded, ardent emphasis on nature, the ecology and human beings’ responsibility as custodians of the planet.

“It’s not something many people were talking about back then,” says Desmond Majekodunmi a.k.a. “Majek,” “especially in Nigeria. But it was an issue we were passionate about and determined to cast light on.”

The album didn’t generate much buzz in the Nigerian market, but it did earn the pair a meeting with the then-very hip Virgin Records in London to discuss a possible major record deal. “So we went to Virgin and the guy listened to it intently. He’s saying ‘Well, the voice is great. And I really like the music, but… every single song on the album is about the environment! Can’t we do maybe just… one song about the environment and then do some, you know, commercial material?’”

Faced with this proposal, standing at the crossroads between abandoning their values to access potential international stardom and holding firm to those values in relative obscurity, Sheila and Des Majek instinctively understood that there was only one pragmatic choice for them to make.

“We walked out,” Majek says. “Just like that, we walked out on Virgin Records and never looked back.”

Some three decades later, Majek looks back on that brash decision from the perspective of maturity. “Yes, that was youthful arrogance,” he concedes. “Of course we should have compromised a little bit, maybe done half and half, some environmental material and then some other stuff. Given them at least a commercial single. That probably would have been the sensible thing to do. But we were so caught up in our passion, we were like ‘Raaaaaaahhhhh we’ve got to save the world!!!’”

“I don’t regret it, though,” he says.

Mother Nature

As Majek talks about the ups and downs of life, he never sounds regretful but rather equanimous, and deeply grateful. He and Sheila were together for over twenty years, having first met in the nineteen seventies in Lagos, when he was an up-and-coming technician in the music industry and she was a promising young vocalist. Their respective paths through life that had brought them together, however, could not have been more different: While Sheila had had a hardscrabble upbringing with her bohemian parents, Desmond Majekodunmi had grown up in relative privilege in the southwestern city of Ibadan, where his Nigerian father was a doctor and his English mother was an educator. Later in his teens, his parents sent him to continue his studies in Ireland. (“I think that must have been around 1967,” he says, “because I remember that soon after I got there I attended the Jimi Hendrix Experience concert at the Olympia in London—amazing show!”) It wasn’t long before he joined a band himself and started gigging around the Dublin club circuit and contemplating a career as a professional musician.

“In 1969, I met this guy named Phil Lynott who was singing with a band called Skid Row,” Majek says, “and he decided he wanted to start his own group.” Lynott in many ways cut a rare figure that paralleled Desmond’s in the Dublin music scene. They were about the same age, both tall, both from mixed, black and white parentage. “He needed a drummer and of course I had been playing drums since I was in a pop group in high school.”

“So I came in and auditioned, and I got the green light,” he continues. “But then something went off in my head and… I started thinking about my parents. I just thought about my father sitting at a dinner party, and everybody is talking about their successful children. You know Nigerian parents, they want you to be a doctor or a lawyer, an engineer… especially back then! So everybody is talking about what their children do, and then ask my father ‘What does your son do?’ ’Oh, he’s a drummer in a rock n’ roll band!’ Ugh… I just couldn’t do it.”

Torn between his passion for music and his desire to please his parents, Majek compromised by studying to become an audio engineer. That way he could keep his foot in the world of music while maintaining a job that suggested relative respectability. After all, the job had “engineer” in the title so it sounded important at dinner parties. Who could beat that? “And,” Majek adds, “I was the first black audio engineer in London.”

Doing his apprenticeship at De Lane Lea Studios at Wembley, he worked with the cream of early seventies British rock, including Fleetwood Mac, Wishbone Ash and Deep Purple. In addition, Majek himself also played with Kokosachi, one of the many London afro-rock groups that sprouted up in the wake of the success of Osibisa. Soon enough, he crossed paths again with his old mate from Dublin, Phil Lynott, and his new band Thin Lizzy, as they were recording in London. “Phil needed a flatmate,” Majek remembers, “so I gave him a room at this place in West Hampstead and we stayed there for a while. We collaborated on songs and stuff, and I engineered their album.” The Thin Lizzy album Majek worked on was the band’s second, 1972’s Shades of a Blue Orphanage but by the time they scored their big hit “The Boys Are Back in Town” in 1976, Desmond Majekodunmi was already moving on, having accepted an offer to work for PolyGram back in Nigeria.

“I helped PolyGram set up a multitrack studio and worked with a lot of artists there,” Majek says. Some of the musicians who benefitted from the Majek Touch in the studio included Sir Victor Uwaifo, pop-soul crooner Perry Ernest, teenage rock idols Ofege and the legendary Fela Anikulapo-Kuti. He also continued to work with artists on the other side of the Atlantic, such as the Jamaican crossover reggae band Third World and their breakthrough 1978 Journey to Addis album. (Majek: “The one that gave them the big hit with the cover of ‘Now That We’ve Found Love.’ I think I actually played a drum track on that song.”) But one of the associations Desmond made during this period turned out to be one that would change his life.

“When I came back to Nigeria, that was when I met Sheila,” he says.

Sheila Andrea Green’s parents—African-American jazz musician Ivan and white American nurse Jeanne—like a lot of beatnik youth in the Eisenhower era, had fallen under the sway of Kerouac-esque wanderlust. They left America in 1957 to trek through Mexico and Guatemala, where Sheila was born in 1960. Over the course of a few years (and a few more kids) they would make their way across Europe before motoring across the desert into West Africa, finally arriving in Nigeria in 1971. As they made their way into Lagos, the family’s rickety van broke down in the middle of one of the city’s infamous “go-slows,” causing a major traffic jam in an episode that got featured in the popular Lagos Weekend tabloid. Immediately, this strange, nomadic multiracial family became minor celebrities. For the next few years, Ivan got work playing with Fela and writing columns about his travels in the Nigerian Punch newspaper. As Sheila came of age and showed signs of being a gifted chanteuse, she joined her father, working with prominent dramatist Moses “Baba Sala” Olaiya and juju superstar King Sunny Ade.

The Greens achieved further fame when Ivan Green’s story took a curious turn: Shortly after his arrival in Nigeria, he was confronted by an old Yoruba woman who insisted he was her long-lost son who had disappeared as an infant back in the nineteen twenties. Green described this meeting in From the Bottom to the Top, he and Jeanne’s third-person memoir, published in 1983:

“Now,” the old lady began, “a long time ago, over 40 years to be exact, my son Bolaji, was stolen from me when I left him with my mother. Oh, it was a terrible thing. For years, I looked for him, spending money here and there. Two years ago, I had a dream. My son returned to me and he brought a wife and five pickins with him. You, are my son,” she said firmly.

“Whoa now, wait a minute,” Ivan said. “I understand your concern for your son, why that would be a terrible thing to happen; but why do you think I’m him? I have no tribal marks like yours. I don’t know anything about Africa except what I’ve learned in the short time I’ve been here. “

“I did not put any marks on your face, but I did put a mark on you so I would always recognize you. Let me see your right arm?” she asked.

Ivan looked bewildered, but he held out his right arm.

“I am correct,” the old woman said, pointing to a mark on his right forearm.

“That’s fantastic,” Jeanne said.

“It’s too far-fetched to be true,” Ivan concluded. “I can’t believe it.”

“It’s true-oh. I, Esther Afoloju Bamijoko say it’s true.” She turned to the women and they began speaking in Yoruba again. Just then, Mr. Kamson joined the group. He spoke at length with the women, and then turned happily to Ivan.

“I see you’ve met your mother,” he said.

“It was crazy,” Majek says. “He had grown up in a foster home in America so he never really had an idea of any family or where he came from before that. And here’s this old woman telling him that he got missing by the riverside when he was five years old. There were a lot of sailors around the seaside then and so they thought maybe the sailors had somehow taken him with them. And now these people were telling him he was back home. So if he wasn’t Nigerian before, the whole family became Nigerian then!”

Feeling Good

Taking on the name “Bolaji Bamijoko,” Green became the living personification of the “back to our roots” mood pervading the black diaspora in the seventies. All of which was good for his visibility, but his focus was on launching Sheila Bamijoko as a star. When Desmond Majekodunmi entered their lives, Sheila had been singing with the Swiss-Nigerian jazz-funk bandleader Tee Mac, performing at his Surulere Night Club and on his weekly television show.

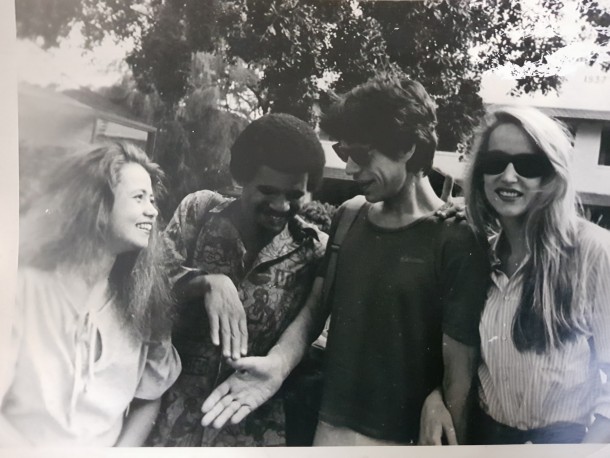

“Sheila had some incredible, incredible talent,” Majek recalls. “Fela bowed to this girl, man. When she sang, when he heard the notes she was hitting, he had to give her that respect!” Other music heavyweights they encountered agreed: “We’d actually met Stevie [Wonder] earlier in Lagos when he came for FESTAC 77, and then we met up again in London. I remember when we went to his hotel room, Marvin Gaye was there, and Sheila sang a bit for them. Man… Stevie was just swaying his head in ecstasy, and Marvin was just nodding, really digging it. That was the effect she had on anybody who heard her voice. Mick Jagger, all of them… they just loved her singing.”

Meanwhile, Sheila was having a different, more intimate kind of effect on Desmond, and he on her. The two fell in love and quickly got married, despite Ivan’s fears that marriage would distract her from focusing on her career. The opposite was the case. The newlywed Majeks moved to Nairobi, Kenya where Desmond had gotten a job as a producer and engineer with CBS, and at the new sixteen-track studio Desmond set up there—the first in East Africa—they started working on Sheila’s solo LP to be entitled African Connection.

“And then Wayne Vaughn who used to play keyboards with Earth Wind and Fire. He came to Nairobi for a one-week holiday and he was staying in the same apartment block as us. He and Sheila hit it off like a rocket. He wanted to take her back to America to tour with EWF! I told her to go, it’s an amazing opportunity. But she said no, no… she can’t just leave her husband behind and go off with these guys.”

“We all collaborated on some stuff together, though,” Majek adds. “There was a song we were working on, called ‘Catastrophe’… Later, when he got back to the States I guess he ended up working some more on that idea with Maurice [White] and it ended up being a big hit for them as ‘Let’s Groove.’”

However, Kenya would change the direction of the Majeks’ lives in even more profound ways, giving them a new inspiration and sense of purpose. “I observed how much of Kenya’s economy was built on taking care of the environment,” Majek says. “Agriculture and ecotourism makes up more than ninety percent of their income. When I came back to Nigeria in the early eighties, I decided that I wanted to become a farmer. So we joined the Nigerian Conservation Foundation and started an agroforestry farm.”

The Majeks continued work on advancing Sheila’s career as she went on to work with South African musician Themba Matebese a.k.a. T-Fire. The release of African Connection, however, was hamstrung by politics. Still, their new commitment to the environment and agriculture took more of a central position in their lives, even becoming the focus of their music as they started to work on songs that would combine the two worlds, and hopefully wake up Nigeria and the world to the importance of protecting the environment. “We had pretty big goals,” Majek laughs.

The result was Green Leaves. While the album is credited to “Sheila and Des Majek,” Desmond mostly plays the background, leading the band and working behind the mixing desk. “I wasn’t allowed to sing on that album,” he says. “She wouldn’t let me sing! So I was relegated to doing some rapping, and if I behaved myself, maybe the occasional backup vocal. I couldn’t sing next to her because she had such perfect pitch… When she’d sing a note, it would be like a shockwave. To sing with her, you have to be very, very precise with your musical abilities, and my ear was just not up to hers.”

Korup Forrest (in Africa)

The album received a relatively low-key rollout on Polydor upon its release in 1989. It just seemed too… different from anything that was going on musically, and the subject matter was alienating. Nigerian listeners were not used to music asking them to think about the environment. It seemed preachy, elitist and distant from what could be considered as the concerns of common people. But the record received a much more enthusiastic response within the environmentalist community, a statement of purpose for the still relatively small, nascent movement in Nigeria. “The people in the Conservation Foundation were quite excited,” Majek says, “and they were very high-level people with access to leadership in the movement around the world. They were the ones who invited the Duke of Edinburgh to Lagos and gave us the chance to play for him, and present him with the album… We played, and we totally blew him away. He was over the moon for the record. At the end of the day, the Palace wrote a letter of recommendation for us to go to England to meet with Richard Branson.”

“And that’s how we got the recommendation to Virgin Records, even though that didn’t work out.”

“But still, a lot of good things came out of it. As a result of all that, we were able to persuade the federal government to establish a Ministry of Environment and set up forest reserves. We had a considerable influence on the culture of environmental protection. We started conservation clubs in the schools, got environmental issues on the education curriculum. We got a lot of work done to protect the Nigerian environment. In retrospect, not nearly enough—we still need to do far, far, far more. But at least it was a step in the right direction. And it continues today.”

Unfortunately, one thing that did not continue was the union between Sheila and Des Majek. The couple had decided to end their marriage by the end of the nineties, but they remained the best of friends as Sheila relocated to the United States. Sadly, she fell ill and died while still in her forties, but Desmond Majek remembers her fondly, and cherishes the time they spent together, and the work they did together. And that is the subject for which he expresses the most gratitude.

“It was such a privilege to have a relationship with an artist as talented as Sheila was,” Desmond muses. “Such a privilege! What an incredible musician. What an incredible person. I’m so glad we were able to do what we did before she passed on. And she’d be very happy about what’s happening now. Because people are finally catching up to what we were trying to do.”

And yes, in Nigeria society is catching up to the message Sheila and Des were preaching years ago, as the government allocates more and more resources to anticipating climate change and caring for the environment. Today, Desmond Majekodunmi heads LUFASI—the Lekki Urban Forest and Animal Shelter Initiative—a twenty-hectare forest park in the upscale Lekki section of Lagos. He also runs the agroforestry farm Majekodunmi Agricultural Projects and the consulting firm Desco Tourism & Trade Developments, producing documentaries and broadcasting a radio show to spread the message of conservation.

But we’re catching up to what they were trying to do musically too: Green Leaves was an album that was ahead of its time, thematically and sonically. And what sounded completely uncommercial and out of place in 1989 sounds fresh and contemporary thirty years later.

So listen to this sinuous, sexy, otherworldly music from Sheila and Des, and if you get a chance… plant a tree today.