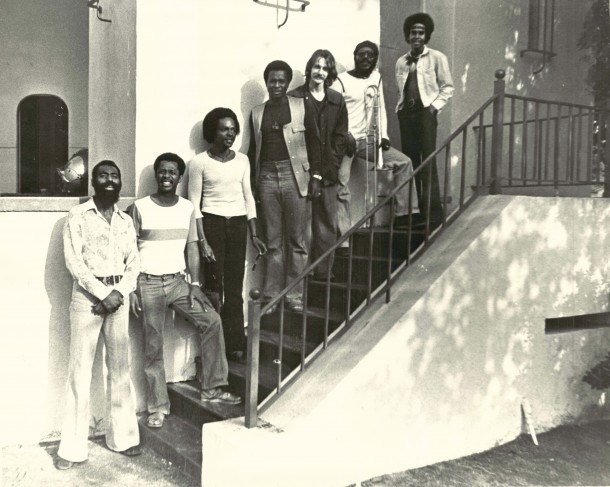

Henry Franklin and band, early 70s

By Uchenna Ikone

The August 1969 “special issue” of Ebony magazine tackled a conversation that could not be ignored in 1969, “The Black Revolution.” These were turbulent times. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated the previous year, the dream of a polite civil rights movement based on an appeal to the conscience of whites seemingly dying with him. A new generation of fiery young activists were demanding “Black Power.” Young writers of the Black Arts Movement were translating the same concept to their work, advocating an aesthetic that was more confrontational, more specifically “Black”: Art that emphasized black self-reliance, self-determination, commitment to the struggle for liberation and the black community’s control of its own businesses, organizations and institutions. In addition to addressing all these happenings, Ebony’s special issue featured “Revolution in Sound,” an essay by poet AB Spellman contemplating similar developments in the world of jazz: “The new thing” emanating from the likes of Pharaoh Sanders, Archie Shepp, Cecil Taylor, Max Roach and Mingus. A new kind of spiritually-inclined music that was thoroughly Afrocentric yet planetary in scope, that was inward-looking yet expansive, that quested for black self-definition and a transcendent “positive black-loving experience.”

In “Letter to Atlanta,” a separate essay published in the Black Arts journal Cricket in the same year, Spellman expanded upon the idea of jazz as a vehicle for a new black consciousness, stressing that for jazz to thrive in this new revolutionary reality, black musicians needed to “put together new record companies, community based music rooms, black publishing companies, etc.” “Bringing the music home to the black community, “ he argued was “easily the most pressing problem the music faces.”

Various solutions to this problem were proposed over the next few years. This is a story about one of them. A story about Black Jazz Records.

***

Ebony’s special issue was still being thumbed through in black barbershops and diners in Los Angeles when a guitarist from Omaha named Calvin Keys arrived in 1969, part of the mini-Great Migration of black musicians flocking to the City of Angels at the end of the sixties. At age twenty-six, Keys was a showbiz veteran, having worked as a sideman across the Midwest and East coast R&B, blues and jazz circuits since his teens. Now he was ready to take his career to the next level. “I wanted to make an album,” he says. “It just seemed a lot easier to get that done in L.A. than over in New York.”

Calvin Keys

Los Angeles could be a precarious prospect for the black jazz player. “West coast jazz” was typically identified with cerebral white musicians like Andre Previn, Stan Getz and Bill Evans who piped out “cool” but slightly antiseptic bachelor-pad music. Still, there were spaces where black players with a more “hot” energy could thrive.

Calvin Keys ‘B.E.’

“Now if you came to LA and you were saying something, people would have something to say about you,” Keys explains. “So I started getting calls from different cats, and one of the cats who called me was a man named Ray Charles.”

By 1969, “Brother Ray” was still revered in the black community as the Genius of Soul, the blind visionary whose effortless fusion of R&B, jazz and gospel had catalyzed the expansion of black music’s horizons. “If you came to LA and you had your stuff together musically, Ray was gonna want to see you,” Keys says. “So I got with Ray and I was with him for a few years.”

Keys continues: “When I was with Ray, Larry Gales—the bass player who was with Thelonious Monk—he had moved to LA and opened up a coffee shop, an after-hours coffee shop round the Crenshaw district, Leimert Park. We used to go there and jam all night. That’s where I met Gene Russell, and he said he was gonna start this record label called Black Jazz Records.”

Gene Russell (born in 1932) had a reputation as a fine, Julliard-trained pianist who had worked with artists from Miles Davis and John Coltrane to Zoot Sims and The Three Sounds. He was always looking to expand his range beyond the bandstand, though, and had been involved in the film business—both as a composer and an actor—as well as other forms of enterprise. His new idea was a deluxe record company of Blue Note caliber that for the first time would be owned by black people, staffed by black people, and produce jazz music by black people to be marketed to black people. And it would all be based in Oakland, the city that the Black Panther Party was establishing as the national capital for Black Power.

The idea was very much in line with the ethos of the time. Maulana Karenga was over at UCLA preaching the gospel of the seven Afrocentric principles to guide the rise of the Black nation: Umoja (Unity), Kujichagulia (Self-Determination), Ujima (Collective Work and Responsibility), Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics). Nia (Purpose), Kuumba (Creativity) and Imani (Faith). The Black Jazz concept encapsulated all of them, especially the Kujichagulia and the Ujamaa parts. Even the label’s insignia would convey this idea, depicting two black hands clasped that universal symbol of black mutual sympathy and solidarity: a soul brother shake. Keys was intrigued.

“So Gene asked me, ‘Calvin, would you like to join?’ I said ‘Of course!’”

Gene Russell ‘get down’

***

A lot of Russell’s sales pitch for Black Jazz was slightly over-exaggerated. Press releases for the upcoming label stressed the revolutionary nature of the project, trumpeting that the official launch of Black Jazz in March 1971 represented the first jazz record label started by African-Americans since the Spikes Brothers opened Sunshine Records in 1921. This was certainly not the case: Charles Mingus and Max Roach had started Debut Records in 1952. El Saturn Records had come in 1957 from Sun Ra with Alton & Artis Abraham. John and Alice Coltrane established the Coltrane Recording Corporation in 1966. Pianist Don Pullen and drummer Milford Graves had unveiled their own label SRP (Self-Reliance Productions) in 1967. Even Strata-East, run by trumpeter Charles Tolliver and pianist Stanley Cowell, had slightly beaten Black Jazz to the market in 1971.

But one thing was for sure: There had never been a black-owned label with the scale, the ambition and—most importantly—the operating budget of Black Jazz. Each release would come in prestige packaging, with a consistent modernist black & white design that immediately distinguished Black Jazz product from everything else on the racks. The records’ fidelity was also uniquely opulent: state-of-the-art Stereo-4 quadrophonic sound encoding. Black Jazz’s plush financial and sonic resources had been furnished courtesy of the Glenview, Illinois-based record company Ovation Records, headed by Dick Schory.

Schory, a longtime percussionist in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, was concurrently an executive in marketing and product development at Ludwig Industries. Schory claimed to have designed the Ludwig Drum Kit, the classic starter drum ensemble that would launch a million garage band dreams. In 1969 he started his own label, Ovation Records, reputedly the first label to press a record in quadrophonic sound, earning him the nickname “The Quadfather.” Somewhere along the way he had befriended Gene Russell, and gotten turned on to his idea for a new independent jazz label. According to the publicity material, Ovation was providing financing for Black Jazz as well as distributing the label’s releases. With that kind of support, Black Jazz was set to stand head and shoulders over similar labels. While an indie imprint like Strata-East depended on its artists to raise the funding for the production of their own records, Black Jazz was being spotlighted in full-page ads in Billboard and other trade mags. This was one jazz label with its eyes set on the stars.

***

The first Black Jazz release hit the market on August 1, 1971, an album by Gene Russell himself, symbolically titled New Direction. A tasteful set featuring Russell’s funky and bluesy piano articulation, backed by a combo anchored by bassist Henry “Skipper” Franklin, who would become a fixture of the label’s releases. “Gene was a good friend,” Franklin says, “and I had worked with his group so when he formed Black Jazz, I was the stable bass player and I recorded with most of the groups.”

Franklin’s versatility was an asset, as he had a firm grip of jazz tradition as well as a handle on contemporary popular styles. A native Angeleno, he had started his career at age eighteen with the Roy Ayers Latin Quintet before moving to New York to join Willie Bobo, and then playing with South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela for four years, including on his 1968 breakthrough pop single “Grazing in the Grass.”

“After that, everybody wanted to get paid,” he says. “Lee Morgan had had his big hit with ‘The Sidewinder,’ Cannonball [Adderley] was getting funky, Miles, Donald Byrd, everybody was switching to more popular music.”

“So when Gene asked if I wanted to do my own record as a leader, I did it,” he says, referring to his LP, The Skipper, Black Jazz’s seventh release, issued in 1972. The album finds Franklin doling out some strong funky aromas but never drifting entirely into pop, keeping the balance with strong hard bop harmony. “Gene never told me what to play.”

Calvin Keys agrees that Black Jazz engendered a sense of freedom and experimentation. “The first record I did with Gene was Shawn-Neeq, in 1971,” he says. “I had Owen Marshall on there playing what he called the Hose-o-Phone. He had taken a water hose, cut it about two or three feet long, put holes in it and played it like a clarinet! And he did the same thing with a bamboo and called it a Boonet; it made a real high-pitched sound like a soprano sax. We were doing a lot of experiments with the music back then!”

“That was the great thing about Black Jazz, really,” Franklin says. “Everybody did their own thing. Everybody had their own ideas. Gene didn’t want no rock n’ roll, but just play your ass off. He wasn’t thinking about what you had to do, hit-wise, but that’s the best way to get a hit—just don’t think about hits.”

The hits would come to Black Jazz, and sure enough, nobody was thinking about it or expecting it when Black Jazz’s signature stars would arrive in the form of a husband-and-wife duo from Down South with a sound that would transform the texture of modern black American music.

***

“After Dr. King was killed, it seemed all his disciples just scattered to the four corners,” Doug Carn told Connect Savannah in 2013. “We had done just about all we could do in Atlanta, the twenty or twenty-five musicians that were there. A whole bunch of us moved to California at the same time.”

Doug Carn had been living in Atlanta, studying Music Composition at Georgia State University. On the side, he did some work for a music booking agency, writing lead sheets for some of their acts, including R&B stars like Major Lance and The Tams. Born in 1948, Carn had grown up in St. Augustine, Florida, where he took up the organ as a child. He had learned about jazz from his radio DJ uncle but he really got his chops with his first professional band, The Nutones, playing around Florida and southern Georgia at the age of fourteen and gaining a proficiency in a variety of styles.

“In the South there weren’t many jazz clubs “ he told MTV.com in 2000. “Most things took place at Elks or American Legion halls, and when we played you had to play for everybody. Old people, young people, people who like jazz or blues, things that were on the Top 10, so at an early age we were mixing all these things together.” He would find that the sound of Brother Ray would always work on any black audience, though, and later in life he would identify “blind-man’s groove” as the foundation of his musical voice.

At his job at the booking agency in Atlanta he would meet the agency’s receptionist, Shirley Jean Perkins, a beauty who he would find was possessed of a crystalline vocal tone and an astonishing five-octave range. Immediately they struck off a deep romantic and musical relationship.

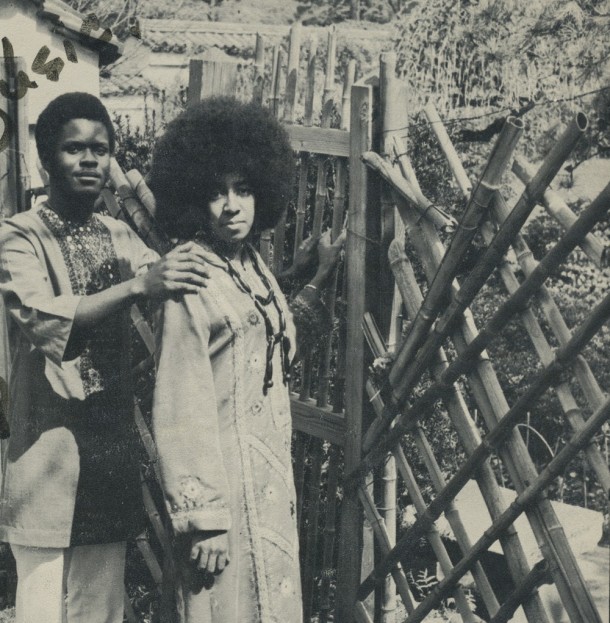

Jean and Doug Carn

Doug Carn released a free jazz trio album on Savoy Records in 1968, but it sank for lack of promotion. Feeling Atlanta was a dead end, he decided to go west. In Los Angeles, he and his now-wife, Jean Carn, situated themselves in the Sunset Boulevard scene, moving into an apartment in a building called The Landmark that was home to several striving musicians.

“Mandrill was in there,” Carn says, “The Chambers Brothers was in there, Janis Joplin had an apartment in there that she used when she came to LA. And these new guys named Earth, Wind & Fire, in five or six apartments. The whole band was there.”

The Carns also befriended organist Larry Young, who deepened Carn’s appreciation for John Coltrane’s devotional epic A Love Supreme and introduced him to a modal approach to playing the organ. With these ideas in tow, he and Jean started demoing an album that would combine the otherworldly spirituality of Coltrane with Carn’s earthy, Brother Ray-influenced groove instincts. At the same time, Doug and Jean also worked with their neighbors Earth, Wind & Fire, who were now signed to Warner Brothers. The Carns contributed to the band’s first two albums (both released in 1971), adding a dreamy, jazzy sophistication to the group’s raw funk. “I guess they wanted me mostly for the organ,” Carn explains. “I played some keyboards, too. Of course, Jean did some background vocals, a lot of overdubs, creating a vocal wall of sound. They were very jazz-oriented, and I guess I was already R&B-oriented a little bit.”

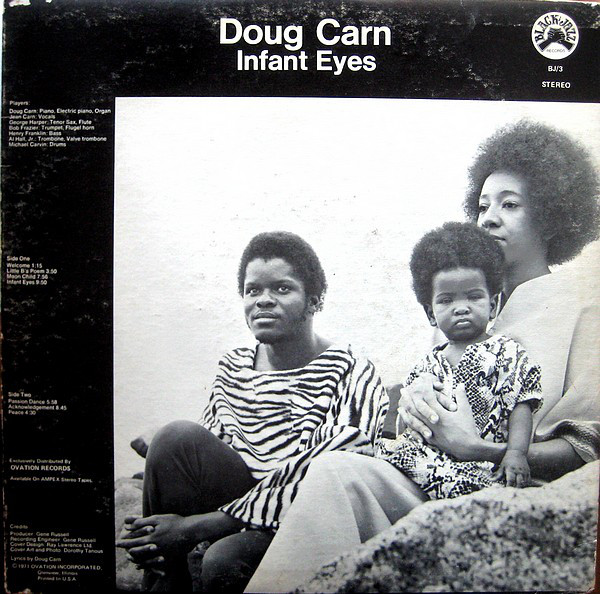

For their own album the Carns were stumped for material. They knew they wanted to present their own interpretations of jazz standards but Doug was bored to death with the customary vocal songbooks. He wanted to try hipper compositions by challenging instrumentalists like Coltrane, Wayne Shorter and Horace Silver… but that would mean composing new lyrics to them, similar to the “vocalese” approach of artists like Eddie Jefferson, King Pleasure and Jon Hendricks who would vocalize the solos of jazz’s most accomplished instrumentalists.

When the demo was done, Doug Carn played it for various labels—Blue Note, CBS, MCA, Impulse!, Milestone—nobody was biting. And then one day, Gene Russell showed up at the Carns’ door. He had heard about this album, and he was interested in releasing it.

“So I said ‘Well, I’ll let him do it just so we can get it out there,’” Doug Carn says. “And I’d get my money back.”

***

The album, Infant Eyes, was released in 1971 and was an instant smash. Its expansive and cinematic sound dripped with love, hope and compassion of a strain that was completely new. Its tone—lush, baroque, Afro-jazz flavored arrangements topped with soaring, operatic female vocals—established a template that was soon emulated by other groups including Oneness of Juju, Nation, Creative Arts Ensemble and even the Carns’ erstwhile collaborators Earth, Wind & Fire. The Carns released two more records with Black Jazz (1972’s Spirit of the New Land, and 1973’s Revelation) and by 1974 they were outselling mainstream jazz giants like Dave Brubeck and Ramsey Lewis.

Doug and Jean Carn ‘my spirit’

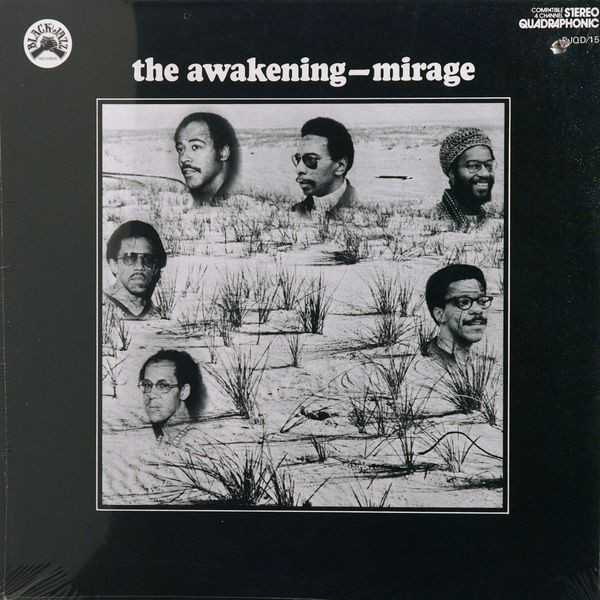

“Doug and Jean were the real thing,” enthuses Tillmon “Steve” Galloway, trombonist in The Awakening. “We never met them, or anybody else on Black Jazz, because we were never in Los Angeles, but we were listening to Doug and Jean because we thought they were happening.”

In contrast to the polished LA vibe of most of the Black Jazz roster, The Awakening came from Chicago, the city that was ground zero for the new revolution in sound, going back to the formation of the avant-garde collective Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians back in 1965. “Chicago was—and still is—the epicenter for a kind of spiritual movement and ancestral heritage of African-Americans,” Galloway says. “Chicago was really different from New York because the jazz scene was still pretty healthy, with a lot of venues to play.” It was in this fertile network of musical activity that Galloway started playing regularly with pianist Ken Chaney, saxophonist Ari Brown, trumpeter Frank Gordon, bassist Reggie Willis and drummer Arlington Davis, acquiring a cult following as The Awakening.

“At that time in Chicago there were the straight-ahead guys but you also had [avant-garde musicians] Phil Cohran and Muhal Richard Abrams who started the AACM,” Galloway says. “I was one of the first members of the AACM and so was Ari. We all liked this concept of ‘out’ music, but kind of straight-ahead. Modal coming from the philosophy of Phil but also having this idea of being able to connect with your ancestors.”

“Ken was a more traditional guy; he was older than us, had us by about six years. He came from a more chordal, harmonic perspective while me, Frank, and especially Ari came from a more modal perspective. We had been sending demo tapes out to different labels, but Ken—he was the businessperson—he somehow hooked up with Gene Russell, and when Gene heard our tape he got back to us right away.”

The Awakening’s debut Hear, Sense and Feel appeared on Black Jazz in 1972, with Mirage following in the subsequent year. Like the sounds of Doug and Jean Carn, The Awakening’s soulful, questing instrumental explorations stood out from the pack. “Gene said that was the reason he signed us, because we were just different,” says Galloway. “All the guys in LA were great, a lot of them had played with the upper echelon of jazz masters, but we were just really grassroots all the way, and I think that was something people found appealing.”

The Awakening ‘mirage’

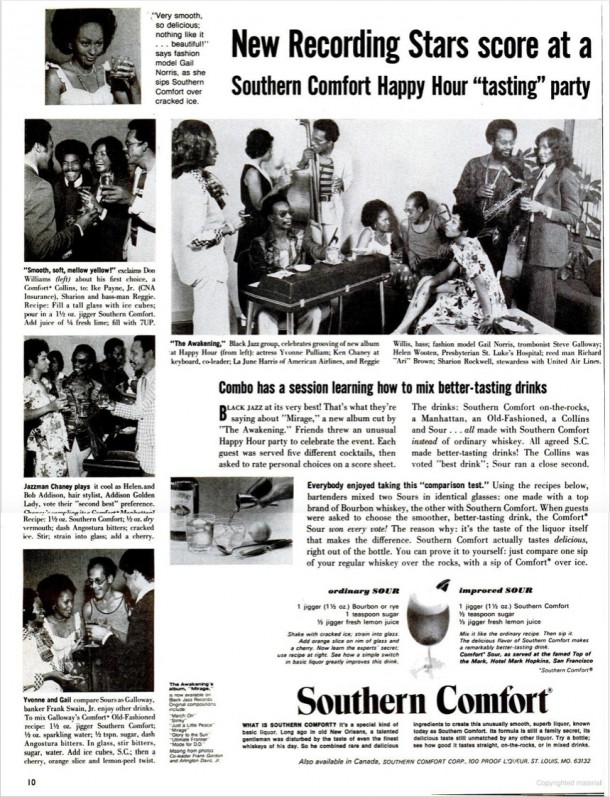

But for a group that was the antithesis of LA glamour, The Awakening hardly expected that soon they’d be starring in a full-page ad, cavorting with a bevy of models in a cross-promotion for Black Jazz and Southern Comfort whiskey. Russell was keeping his foot on the pedal when it came to marketing the label across a range of media platforms. As he would later explain: “Because of the way the industry has turned the past couple of years, it’s important not only to have [the artist] exposed through records but through other vehicles to create consumer awareness. This obviously not only sells records, but for a new artist generates curiosity which in turn builds concert audiences.”

***

For all the artistic accomplishment going on at the label, sailing was not smooth in the Black Jazz business office. Selling records was a struggle in a market in which jazz was steadily losing ground to funk among young blacks. Even Miles Davis was gleefully scandalizing his peers by declaring every chance he got that jazz was dead (“the music of the museum,” he scoffed). Clive Davis, the head of Miles’ label Columbia, recalled Miles advising him “If you stop calling me a jazzman, I’ll sell more.” As cynical as it sounded, Miles Davis was right: the word “jazz” appeared to be becoming toxic and veteran jazz standard-bearers like Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter and George Benson seemed eager to distance themselves from it as the nineteen seventies approached their mid-point. Gene Russell responded by signing Kellee Patterson, a singer and model, recording her for a straight soul album. After all, right from the beginning he had envisioned Black Jazz spinning off a dedicated soul imprint called Grit Records, but it seemed now Black Jazz itself would have to lean towards more popular tastes to stay afloat.

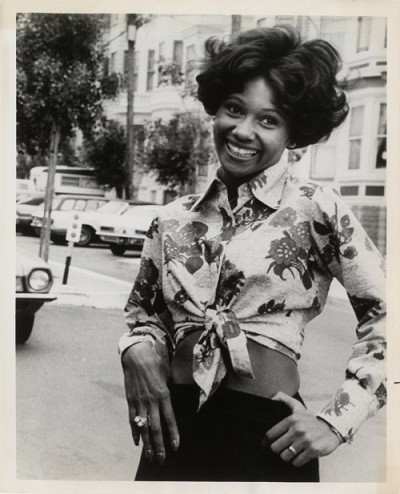

Kellee Patterson ‘see you later’

Moreover, it became clear that Black Jazz was not all that it had appeared to be: Hailed as a shining example of black business ownership, it turned out that Dick Schory and Ovation were more than just financiers or distributors. Ovation owned Black Jazz outright, with Gene Russell serving as a figurehead. This arrangement was actually not uncommon in the early seventies as the major labels scrambled to exploit the black music market. Previous attempts to market directly to the black audience had been hilariously tone-deaf misfires. Efforts to buy out existing black indies had not fared much better. Columbia Records, however, had come up with the perfect solution: Fund boutique labels by signing credible operatives within the black music community to exclusive production deals.

The most prominent example of this phenomenon was Philadelphia International Records, fronted by the respected songwriting/production team of Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. While Gamble & Huff signed acts like Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes, The O’Jays, MFSB, Billy Paul, The Three Degrees and Teddy Pendergrass to the label and produced era-defining smash hits with them, Clive Davis pulled the strings behind the scenes and Columbia reaped the lion share of the profits. Black Jazz, it seemed, was another manifestation of this trend. Gene Russell functioned as the public face of the Black Jazz, but Ovation owned the label in entirety—and even more distressingly, it owned the copyrights to all the music Black Jazz released.

“Those contracts we signed with him, man we didn’t know. We signed our whole lives away,” Calvin Keys laments. “Talking about ownership, publishing… We didn’t know.”

“We did all our business with Gene Russell, but Dick Schory was sort of the hidden figure behind it all,” shrugs Galloway.

“I don’t really know, man. I think [Gene] was just the president. Either that or he owned it in the beginning but couldn’t hold on to it,” Carn told JazzUSA’s Mark Ruffin. “[Ovation] were the people calling the shots. When it finally came down that that was what was happening, a lot of the guys on the label were totally wiped out and dismayed: ‘I thought we were working for the brother, blah blah blah…’ I said, ‘Well, I’m glad to meet you Mr. Whitefolk, maybe we can finally accomplish something and go forward.”

Another blow came when the First Couple of Black Jazz, Doug & Jean Carn divorced in 1973. Jean joined Philadelphia International and enjoyed a successful career in soul and disco over the next few years; Doug recorded one more album for Black Jazz, 1974’s Adam’s Apple, before leaving the label, and Los Angeles, for New York. Black Jazz mustered a last hurrah with bassist Cleveland Eaton’s Blaxploitation-flavored jazz-funk LP Plenty Good Eaton from 1975; it featured “All Your Love, All Day All Night,” an instrumental workout on The Temptation’s “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” that became an early hit in the emerging NYC disco underground. Eaton was subsequently absorbed into the main Ovation label, releasing disco records there until the end of the seventies. In 1976, Ovation also released one final album each of the Carns, Gene Russell, The Awakening, Rudolph Johnson, Calvin Keys and Henry Franklin—all of them compilations recycling their previous Black Jazz recordings. And then that was it: for all intents and purposes, Black Jazz Records had quietly faded away.

Jean & Doug 2019 NYC

The ever-enterprising Gene Russell was not yet finished, however. Almost immediately he formed a new label, Aquarican Records, and produced an album by Native American rock singer Cheyenne Fowler. He continued to manage Kellee Patterson while promoting his latest discovery, a singer named Talita Long (whose daughter Nia Long would become a prominent movie star many years later). Unfortunately, as he was preparing Long’s Aquarican debut, Russell suddenly died in 1981 at the age of forty-eight.

Through the years, the legacy of Black Jazz would gradually recede into the mists of memory until those amazing records were unearthed, revived and revered by a new generation of crate-diggers, beat makers and groove aficionados. That legacy is also kept alive by the surviving players who helped weave the musical magic. All have had long, productive and rewarding careers, but they all remember their time with Black Jazz as truly special.

“The label was right on time,” Henry Franklin maintains. “It was definitely on time for me and all the artists that were on it because it helped everybody’s career and it achieved a lot of recognition all over the world. Every time I go overseas people want me to sign a copy of one of those records.”

“I’m grateful for what Gene did with Black Jazz because it gave me the opportunity,” says Calvin Keys. “Just being able to get a record out in your name as a leader… Do you know what that meant back then? That was huge!” Calvin Keys pauses, and adds: “But more than that, it gave us hope. Just the idea of a label like that existing gave hope to the music and hope to the community that there was a change in the air. It was all about the message.”

“That’s what Gene Russell set out to do, and I guess that’s the most important thing of all.”

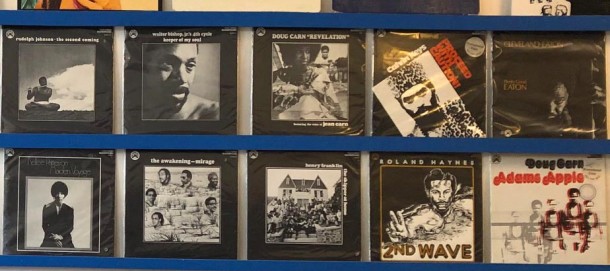

BJ1 – Gene Russell – New Direction

BJ2- Walter Bishop Jr. – Coral Keys

BJ3- Doug Carn – infant eyes

BJ4- Rudolph Johnson – Spring Rain

BJ5 – Calvin Keys – Shawn-Neeq

BJ6 – Chester Thompson – Powerhouse

BJ7 – Henry Franklin – The Skipper

BJ8- Doug Carn – spirit of the new land

BJ9- The Awakening – Hear, Sense And Feel

BJ10 – Gene Russell – talk to my lady

BJ11- Rudolph Johnson – The Second Coming

BJ12 – Kellee Patterson – Maiden Voyage

BJ14- Walter Bishop, Jr.’s 4th Cycle – Keeper Of My Soul

BJ15- The Awakening – Mirage

BJ16 – Doug Carn – Revelation

BJ17 – Henry Franklin – The Skipper At Home

BJ18 – Calvin Keys – Proceed With Caution

BJ19 – Roland Haynes – 2nd Wave

BJ20 – Cleveland Eaton – plenty good eaton

BJ21 – Doug Carn – Adam’s Apple